Race and Racism Across Borders

Crossing borders—whether by traveling away from home or encountering new people where we live—can confirm or upend our viewpoints on race, racial stereotypes, and racism. What follows are select prose, poems, and visual art submitted by Cornell students and alumni who gained new knowledge about racial dynamics by crossing a literal or figurative border.

Entering America

Ekaterina Landgren, PhD ’22

JFK, LAX, and Boston Logan Airports

From a young age, my Russian parents instilled in me that there are few things worse than not having the right papers. My father traveled with thick folders of supplementary materials. A passport was just the beginning. Passport control was a trial, and during that trial, any document—from birth certificate to apartment title—could be requested, reviewed, and rejected. Crossing the border was a game of chance rigged against us. You had to count yourself lucky and feel grateful if you made it through.

Passport control is a test—a regular test in my life, but too high-stakes to be routine. When my flight would land in JFK, the passengers would be separated into citizens, green-card holders, and then the third, most winding line to the gatekeepers, to which I was always consigned. And when the time of my brief audience would come, I would try to look my most law-abiding and amiable.

My existence is reduced to the documents, and the ostensible exercise is to match those documents. I start performing the paper version of myself. I take my glasses off to match my photograph. I give bland answers to what I study. I prove my English proficiency. I meekly thank the agent for the advice to study more and party less. As I press my thumb to the fingerprint scanner (in just the correct way), I myself feel flattened, reduced, going through a narrow bottleneck waiting to be allowed to become a person again. Until then, I am the platonic ideal of a student, with my eyes set on the American dream, looking past the detail that I won't be allowed to stay past my own graduation. I am unremarkable and unexceptional. I am but the physical manifestation of a folder of papers because personhood is bestowed only on those who pass the test.

Passport control is a test, and once I’m in it, the papers that seemed all-important feel silly. They are an amulet, a charm, and having faith in them was an act of superstition. Under the scrutiny of a border agent, I am suspect, and so is every crease on my I-20 form, every smudged arrival stamp in my passport. I wait for an impossibly long time. I am waved through. The border agent assumes a fake accent and tells me not to drink too much vodka. I swallow my pride and scuttle to pick up my luggage. Once again, I am lucky. Once again, I made it through. Once again, I am grateful. I feel relief, but I feel smaller for it.

For eleven years, I have been required to depart annually to renew my F-1 visa. Every time I reenter this country, I am asked who I am, and why I deserve to continue living the life I have built. The question and the threat echo year after year and stay with me.

Ekaterina Landgren is a PhD candidate in applied mathematics from Russia. She works on models of climate, planetary ice cover, and atmospheric dynamics.

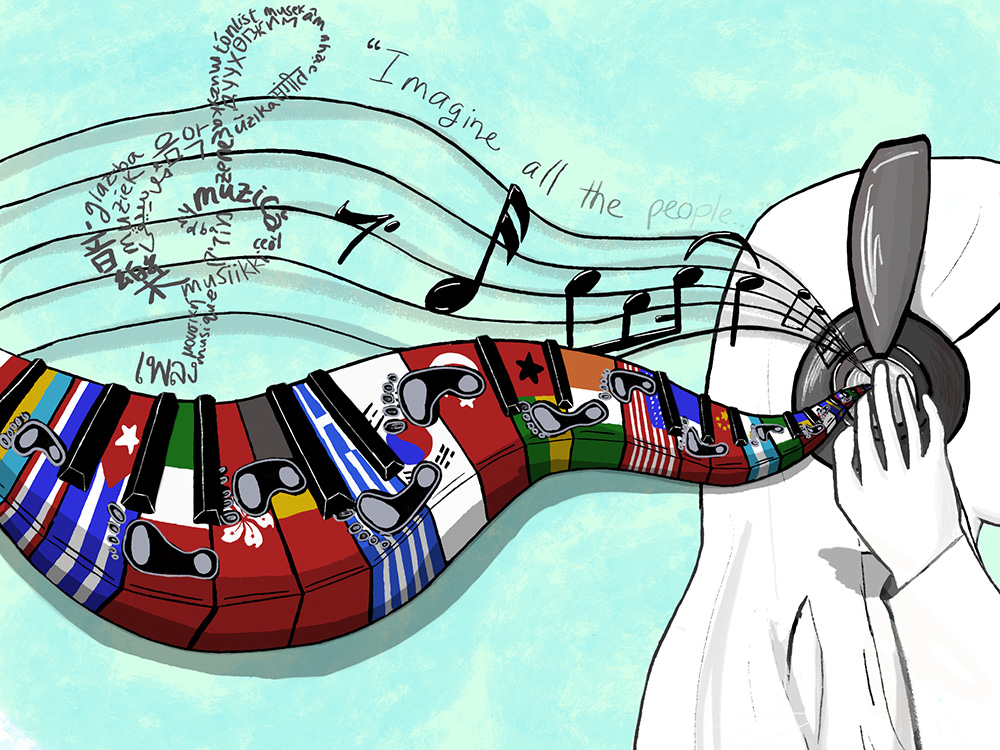

Music, the Universal Language

Carissa Kwan ’19

United States

Carissa Kwan is an Asian-American who is passionate about exploring science, experiencing the arts, and promoting world sustainability.

Stretched Thin

Maxwell Zheng '23

New York and Baoding

She gestures for me to come through the door. There's a xiao pin show on, it’ll be fun. I catch pieces of jokes and try to nod along. I fall asleep because I’m still dao shi cha na.

She shows me which cubby is mine. She tells me that my name is zang and I accept it. This person who looks after me and speaks in a nice singsong way has replaced my name, and I am fine with it.

She hands the skewers to my aunt and asks why I’m not in school. Xiao yi explains that I don’t go to school here as I nibble at the tang hu lu. I hold the seeds in my mouth until I can scatter them in the little square of dirt, vowing to return when the vines are curling around those mildewy apartments.

She and I sing together. We struggle through the pronunciations and laugh at each other's falsettos and I realize she's just as tense as I am. When we're not rehearsing, we watch dumb movies and try to imitate the different accents.

She asks if I remember her name. I peer into her face and I know that this is my gu gu. She laughs it off, and we go cook some shui zhu yu but as I'm zuo guo, I overhear her telling my mother I need better Chinese education.

She tells me that those other boys are going to apologize to me. I don't understand the fuss but I stare at my decidedly beige desk as they mutter that they won’t do the thing with the eyes again.

She looks like my lao lao. A stranger who spends her days in dreams of dirt and fire. A stranger whose expression I can't read, who quietly clasps my hands as she stares straight ahead. Maybe that's why I stood impassive at my mother's side as we burned zhi qian, why I've never lost a loved one.

She snaps. Did I ever gei ni shuo, when we lai America we only had 200 mei yuan. It was hao ji nian worth of savings, but it was stretched thin.

Maxwell Zheng enjoys writing things down.

The knowledge that we are

Tina Lam, MFA ’22

Montreal and Ottawa, Canada

I recall I was a naive eight-year-old the first time I internally struggled with the notion of identity. Walking back from school, my younger sister shared with me that her kindergarten teacher had asked the students to talk about where they came from. When her turn came to reply, she enthusiastically yelled out: "I’m Haitian!"—upon which her classmates began to roar in laughter, sneer, and retort loudly: "No! You are not! You are Chinese!" She had been deeply troubled by the brash remark. She had innocently repeated what the three previous students had replied. Why was she ridiculed while the others’ answer was approved by the rest of the class?

When I began kindergarten, I did not speak the language of the dominant culture where I was born. My mom describes the refugee camp where she stayed in Cambodia as a frenzied auction house where various countries would issue sign-up sheets in order to claim the dispossessed. The sole rumor she heard about Canada, about Montreal, was that people lose their ears and nose from frost, but that gamble still immeasurably outweighed what she had previously endured. We grew up in an “ethnic” ghetto rich in cultural heritages, making us take for granted that people do not look the same. Our neighbors were grateful, and therefore kind.

My first day of elementary school marked me; I learned that we were not all equal. The teachers instructed a few students to stand apart from the rest of us while calling out attendance. All the other students, myself included, stared quizzically at this smaller faction. Within the ostracized, a churning embarrassment suffused the faces of the older ones, an affliction that years later I would learn to recognize as humiliation. These students were cast aside into the French as a second language classroom, and those who escaped over the years to integrate the regular classes made it a point of pride to remind those around that they were now like everyone else, repressing the distress of having been subjected to inferiority. I again witnessed this casual linguistic hazing when we moved to Ottawa to learn English; I palpably felt the anguish, the wish to make yourself small, invisible. Despite the best of intentions and the preaching of diversity, the meaning of difference is taught early on at school.

The violence of imposed alterity, the othering of the discriminating gaze, scars deeply. Oftentimes, the latter is introduced at a much younger age than most are willing to admit, especially because the truth is often too conflicting to accept. The divide is real between those privileged to be recognized with esteem for voicing their truths and those who are indifferently erased by being subjugated into silence. Children learn that difference is deleterious, and the society in which they grow up reaffirms their fears. If there is any hope for difference, it should begin with informed education. That onus rests with those who impart knowledge at school, but most crucially at home.

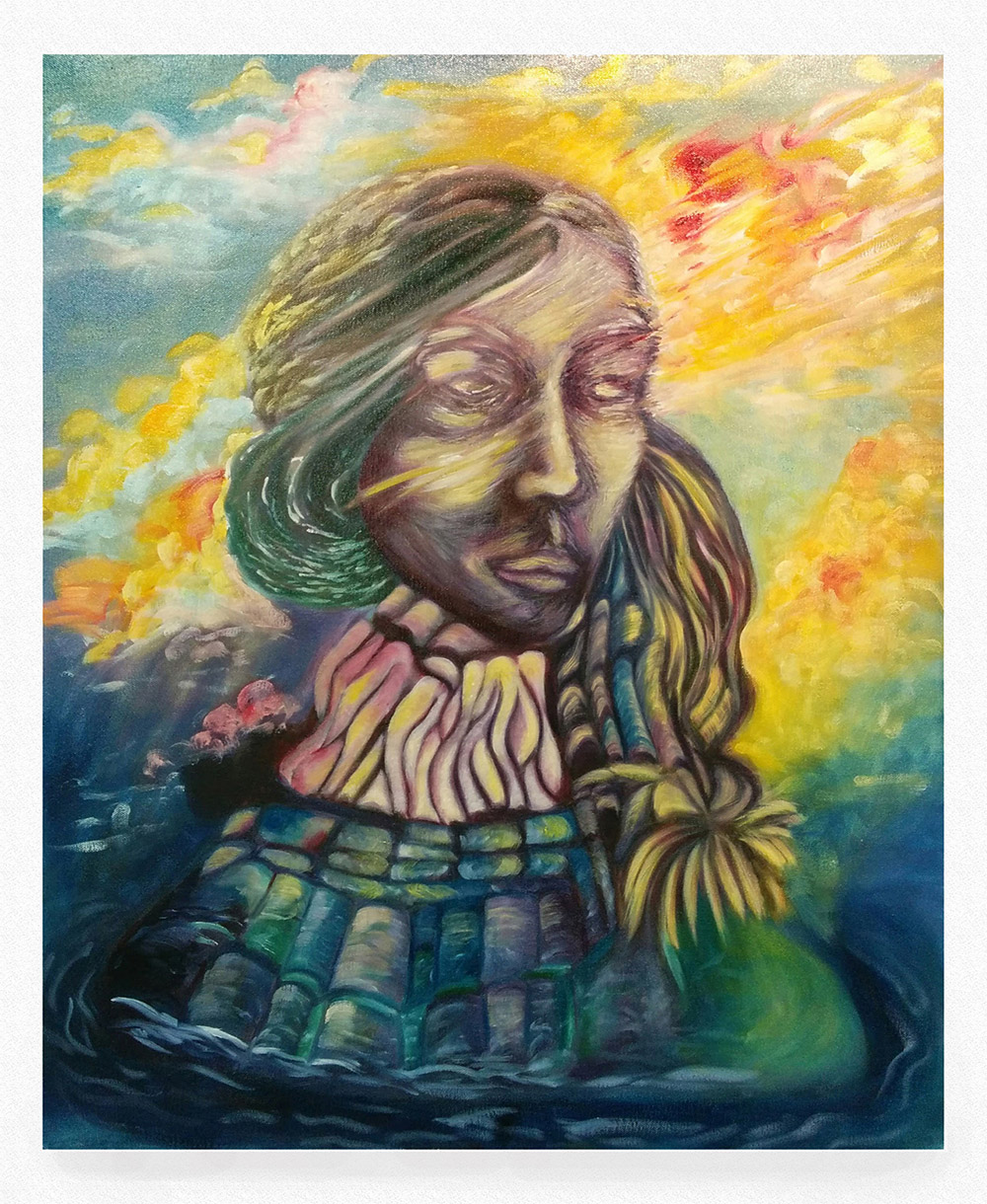

Sun Wind Sister (2017)

Tina Lam is a perpetual learner, a Cambodian-Chinese-Canadian from Montreal, and a Cornell MFA candidate who previously earned a PhD in chemistry.

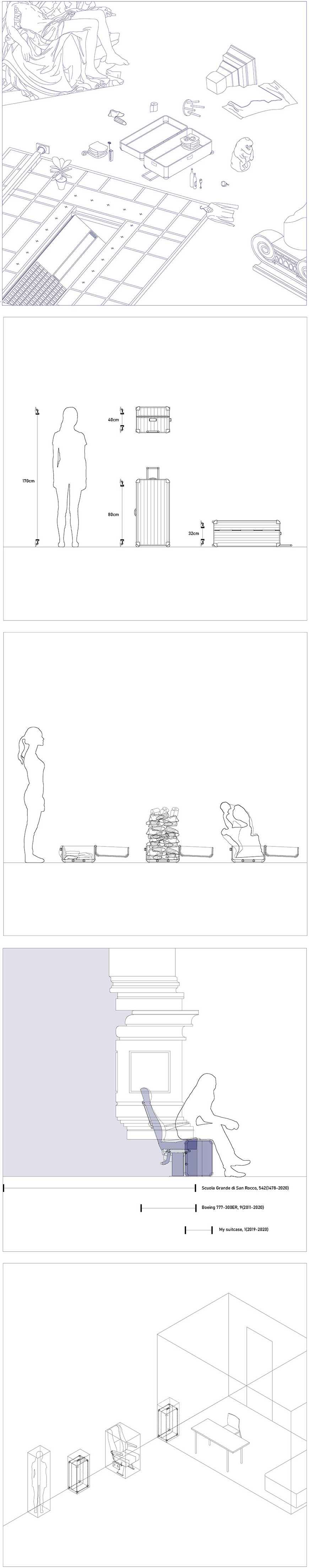

Leaving Rome

Lucy Ding ’22

Rome — Ithaca — Shenzhen — Beijing

Lucy Ding is fourth-year BArch student from Shenzhen, China, currently Studying Away in Beijing.

Flight

Eniola Oladipo ’21

Flight to New York City

Ravines are laced with placid nods,

The landscape is a noiseless sky.

Islands of humans are fastened to chairs,

Threshing measures of silence, counting hours in flight.

Each person has sloughed off pedantic pursuit,

Each life is condensed in a seat row and letter,

Accents careen in rare flecks of speech:

Petitions for quiet or water or dinner.

Here, humans are unobtrusive and shy,

Transfixed in the languor of being unknown.

Passports concussed in a sleeve or a pocket,

Are absolved of distinction; affront or renown.

As seat belts unclasp and the aisles fill with bodies,

The land is consumed with a badgering wind.

Stares haggle status as bliss is relinquished

And torrents of barter for stature begin.

Eniola Oladipo is a senior studying human biology, health, and society and minoring in global health.

Systemic Racism in the Workplace: A Cry

Onyinye Akujuo, EMBA ’22

Texas

In my life, I have on rose-colored glasses:

I grew up seeing only opportunity and no employment fascists.

However through systemic racism, all A's, no matter how hard the classes,

I am told I got into the Ivy because of affirmative action.

I come with education however I am seen as not qualified.

I come through with my experience yet see the rejection with the lies:

I am sorry you were not qualified enough, or please try again next year.

However, I see my lighter-hued counterparts being hired with less,

To think that I have the audacity to have pride in my chest.

As a woman, I am told to not be emotional,

As a personal of color, I have battled with imposter syndrome,

At work, I want ambition and others see attack.

However because of the color of skin, is there something that I lack?

Am I not worth the same as my white counterparts?

Maybe it's because I am black,

So I decide to straighten my beautiful afro curls.

Have to reserve my bravado,

Smile all the time with my teeth and put on the pearls,

Strangle my throat with assimilation, which is the only thing to get me through this racially skewed world.

While I suffer in silence, what we need right now is ally-ship:

When you see me struggling at work, support me at the hip,

When you are in a space of privilege provide the avenue for growth,

Don't just sit back and watch as I go for broke.

Help me to speak up when others can't see

How poor diversity employment practices are affecting people like me.

Stand up and let's start with the inequities!

Then let me challenge you to involve me in your opportunities.

I need the inclusivity!

Pay me in equity! Promote me!

Support me, support us,

Support Diversity.

Onyinye Akujuo is a New Yorker living in the South and wondering, "How did I fall in love with cowboy boots?"

The Different Shades of the Dream

Manasicha Akepiyapornchai, PhD ’22

Thailand

Manasicha Akepiyapornchai is a fifth-year PhD student in Asian studies from Thailand.

גופי עדיין גופי (体)

Kristi Lim ’21

Jerusalem

my body, with more suspicion:

media so talented even i fear

my body down the street.

our tay-sachs, blood

money-fangled. excess more

susceptible, is

yellow.

my body as transit: farewell heat to strangers.

sharing heat with strangers

cheek to cheek. thirst closer until

i am the one to back away —

unprecedented! into different

feverable objects transmutes

my body. yell: No, no, NO,

libido. yellow.

my body as tired. cells overwhelmed by: קפה, 咖啡,

coffee. bitter of my breath radioactive material.

the rest of my body vigorously scrubbed

by generous eyes. thank you for

your cleansing. but i have not come

to alarm you. on this train

only to ride it. yellow.

Kristi Lim is a Singaporean who spent the pandemic re-experiencing being ethnically Chinese (from "fuck you, China" to yellow-fever incidents) studying abroad in Jerusalem.

Recognizing Who We Are

Valeria Gomez ’23

McAllen, Texas to Ithaca, New York

Coming from a small suburban town on the southern border of Texas filled with Latinos and thriving on Mexican culture, I never understood what being in a white-dominated city was like. I grew up in Mexico and moved to the United States at the age of six. Moving to the United States was a drastic change that I was so excited for, but nothing like the change I experienced coming to college in New York.

When I came to Cornell, seeing the diversity of Asians, blacks, whites, and Latinos was eye-opening and fascinating—it was so beautiful to me. However, as I began to speak to more people, I slowly began to notice the social dynamics of the school. People here separated themselves into talking to people of their own race or color and I could not understand why this phenomenon occurred.

Before I decided to commit to Cornell, I visited the campus for Diversity Hosting. I was hosted by a black female who I thought was sweet and overall a beautiful character—I truly looked up to her. Yet, she only hung out with other blacks and began to describe to me how "white people" did not welcome her enough and were not her friends. I assumed she was overreacting and there was no way this was real, yet I was mistaken.

Coming in, I made friends with whoever I thought was sweet and welcoming, and I did not see race or color. However, as a sophomore, I realize now that most of my friends ended up being of minority races. When I realized this, I understood that I was not aware that racism was truly existent and affected many and would therefore affect me, as well. As I continued to observe this phenomenon, I realized that the world is flawed and unaware of its flaws. Before I stopped to think, I did not notice the dynamic of my friend group even once as a freshman, as I was oblivious to racism and now realize that I truly stand with the minority race. The people I have met at this school have opened my eyes to the problems within our nation and I recognize that this is a conflict that needs to be addressed.

For 17 years of my life I was closeted in a bubble of Latinos who welcomed me at every corner, and I had no awareness of racism. This is not true of everywhere else. This world needs change and this change must happen now.

Valeria Gomez is a sophomore studying nutritional sciences from McAllen, Texas.

Bad Hijab Day

Duaa Randhawa, MPS ’20

Central Park, New York City

Duaa Randhawa is a first-generation daughter of Pakistani immigrants, by way of Queens, New York. She is a proud alumna of Sarah Lawrence College, Oxford University, and Cornell. Her poetry has been accepted for publication in an anthology titled New Moons: Contemporary Writing by North American Muslims, from Red Hen Press.

To the Final Pulse in Our Veins!

Samiha Hamdi, MPS ’21

Panama, Pakistan, the United States

This poem and essay are inspired by Intifada and resistance writer Samih Al-Qasim. A book of his poetry, All face but mine, and a poem "Address to the unemployment Bureau," with the line "to the final pulse in our veins," are both referenced.

We are the waterless Ocean;

the wingless bird;

the scaleless snake

who creeps, creeps.

Whose waves keep crashing,

down, down.

All faces but mine

torn away from homes we never knew.

our histories as foreign countries,

as borders, erased and militarized;

as imaginary as the ones we cross today.

we fill ourselves so that we may be;

our self-imposed shackles that bind us to emptiness;

we break

we resist,

"to the final pulse in our veins."

In Panamȧ, I was "la Gringa." In the U.S., I’m “Indian.” In Pakistan, some might call me "gori." All of these and none of these are true. Every day, I decide whether to cross a dangerous border within me or to reside in a comfortable, yet slightly ignorant position. Do I choose to recall the pain and trauma caused by the depths of colonization, by the insidious roots of white supremacy, and by the subjective system of othering? Do I engage with the thought of not feeling Pakistani, nor “American”? Can I walk away? Or, are we confronted with the history of white supremacy and racism in everything we do? Do we, especially POC across borders, have the privilege of escaping racism? This racism is not an isolated concept or incident. The history and ubiquitous nature of colonization flows through our veins. Only through acknowledging this collective trauma can we progress towards liberation.

My experiences abroad, especially in a rural community in Panamȧ, taught me more than anything about community and solidarity. It taught me that maybe the injustice we see is based on othering: on deciding that someone is inherently not like us, is different, and unworthy of understanding. My community in Panamȧ acknowledged me as an outsider, but more so, they acknowledged me as one of them: as a necessary member of the community. This transcended language barriers and imaginary borders. My identity as a Pakistani-American is more than just an identity: it's a way for me to cling to a culture and a home that I’ve been ripped and isolated from, one that I've never known. It's a way for me to build the bridge across the warring borders within me. Walls were raised around me the moment that Britain's 100-year colonial rule of (now) Pakistan began. This belief that anyone being is supreme over another is a root cause of racism—one that transcends borders. It is this belief that exploits the vulnerable, the tired, the poor, the sick, in search of greater power: power that seeks to erase a rich cultural history and violently tear families apart.

In working towards collective liberation from these self-imposed shackles, we resist. We resist in solidarity, across imaginary borders. We resist with the Palestinian Intifada, we resist to end SARS in Nigeria, we resist with George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, and the millions that go unnamed. We resist with the Uighur Muslims; we resist it all with our inherent sovereignty, to the final pulse in our veins.

Samiha Hamdi is an anti-colonial, anti-oppression, and self-love enthusiast who works toward collective liberation with a compassionate heart.

One Summer

Alexandra Li ’23

New Jersey

I eat rice with a spoon

And cheetos with chopsticks.

I watch Xi Yang Yang

And listen to Ed Sheeran.

My identities as an Asian and American

Are interconnected and intertwined.

I grew up in a community

Where the color of our skin

And the foods we brought for lunch

Were numerous and diverse.

I never stuck out

Because we all did.

People from all backgrounds and walks of life

Filled the hallways of my school.

One summer,

I went on a road trip with my family.

We stopped at a nearby Walmart,

And suddenly

I felt alien.

Customers looked my mom and I

Up and down.

They stared whenever we spoke Chinese,

Making me feel self-conscious

Of my Asian heritage

For the first time

In my life.

Since then,

I became more aware of

How "Asian" I was with my friends

And how "American" I was with my family.

Suddenly,

It felt like two identities

That I couldn’t reconcile,

Like oil and water.

But then one summer,

Movie posters and magazine covers

Of the cast of "Crazy Rich Asians"

Filled the shelves of stores

Like that one Walmart.

Suddenly,

I didn’t feel so alien anymore.

Constance Wu and Awkwafina

Were stars that looked like me:

The faces of a Hollywood movie

With an all-Asian cast.

That was the first summer

Where I saw my parents

Excited to go to the movie theater,

But that wasn’t the last summer.

"The Farewell" came out next,

And once again, my parents

Giddily bought tickets for a movie

With stars that looked like us.

Since then,

I am still aware of

How "Asian" I am with my friends

And how "American" I am with my family.

But now,

They are two identities

That complement one another

Like peanut butter and jelly.

I am Asian-American,

And proud.

Alexandra Li is a sophomore who loves sushi, corgis, and spending time with friends and family.